A familiar face emerges from the dark, striding into the warm embrace of a flickering orange street lamp on the edge of town. He carries a white box and a toothy grin, “Erik, you have to see. They are here.” Peeling back the tattered cardboard flap, a flutter of red and white feathers leap forward and crash to the ground. The momentary panic subsides and pride creeps back across Wahid’s face as he controls the young bird and places it back with the others. Six pairs of eyes stare with curiosity from the small white box.

A familiar face emerges from the dark, striding into the warm embrace of a flickering orange street lamp on the edge of town. He carries a white box and a toothy grin, “Erik, you have to see. They are here.” Peeling back the tattered cardboard flap, a flutter of red and white feathers leap forward and crash to the ground. The momentary panic subsides and pride creeps back across Wahid’s face as he controls the young bird and places it back with the others. Six pairs of eyes stare with curiosity from the small white box.

For any, these six young hens will look like any other chicken that can be found roaming the village, perched on a compound wall, or making an unexpected visit to my class; for Wahid, these chickens are so much more than that: they are new, they are exotic, and they are proof that a long-standing ambition has come to fruition

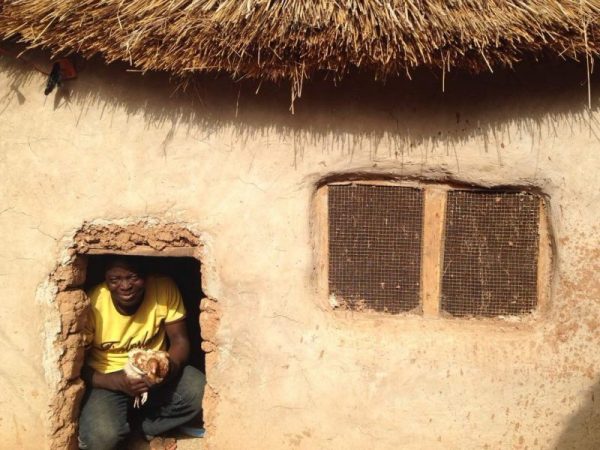

Wahid mentioned to me in October that he had lost a lot of young birds to disease, the elements, and to predators. He, like every other farmer in Cheshegu, raised his poultry extensively. Occasionally finding an egg to cook or sell; rarely even having enough birds survive to maturity to sell at the local market for additional income. His family’s poultry was a sense of pride, but was not a reliable source of income. We decided it was time to try something new, and in December we began the process of building a small poultry house to begin an experimental intensive poultry project for his family. Mixing mud, packing bricks, drying bricks, moving bricks, stacking and gluing bricks, weaving a thatch roof, covering the room with cement, and building a door—construction was no simple feat, but an excitement burned in the neighborhood and brought together many of our family and friends to make things run smoothly.

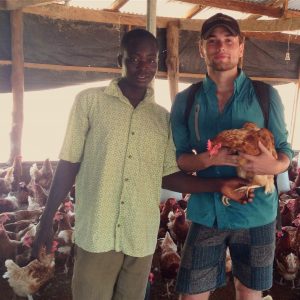

Now, seven months after Wahid first mentioned his desire to change the way he rears poultry, he has a layer house, a smaller house for young birds, and six new laying hens to begin his experiment. He even has a mentor with a commercial poultry farm 35 minutes down the road, and—thanks to seeing that farm in action—has plans to expand this coming year. Six chickens in a mud house may seem like a small accomplishment, but from here in Cheshegu I can testify that it means so much more. For now, a fire of creative problem-solving

Now, seven months after Wahid first mentioned his desire to change the way he rears poultry, he has a layer house, a smaller house for young birds, and six new laying hens to begin his experiment. He even has a mentor with a commercial poultry farm 35 minutes down the road, and—thanks to seeing that farm in action—has plans to expand this coming year. Six chickens in a mud house may seem like a small accomplishment, but from here in Cheshegu I can testify that it means so much more. For now, a fire of creative problem-solving

burns bright in a farm in Cheshegu, started by a spark of imagination and fueled by a supportive local network of family and friends; all I had to do was throw some kindling on and watch the flame grow.

Erik Jorgensen received a bachelor’s in Animal Science from Cornell University. Before becoming an AgriCorps Fellow Erik served as an agriculture affairs intern in Washington, D.C. and a cheese production intern in Italy.